In Part 1 of my book review of Dr. Kruger’s Bully Pulpit, I spent some time highlighting important themes from the book to give us a better understanding of what spiritual abuse is and what it may look like. In the second half of this review, I want to more fully consider the implications for Christian conciliators and how we may best help victims of spiritual abuse.

How Allegations of Spiritual Abuse Affect the Mediation Model for Christian Conciliators

Some Christian conciliators have made the mistake of treating parties to conflict as if they have all contributed equally to the conflict. Kruger cites a Christianity Today report where a debarred Christian Conciliator made mistakes of not establishing the facts and assuming that wrongdoing was equal on both sides, even when there were allegations of abuse (p.71). The Christianity Today article is right in stating that advocates for conciliation say the mutual confession of sin is not an appropriate starting point in response to an injustice such as abuse. Consider the folly of having Pharaoh and the Israelites mediate a dispute and asking the Israelites to do a speck and log list in their conflict coaching.

Kruger is right on in his subsection “An Improper View of Reconciliation: Just Meet with the Monster” in chapter four of his book. Kruger says this:

“[The] eagerness to establish peace sometimes leads churches to rush the victims of abuse into a reconciliation process with the abuser that is ill-conceived. Because churches often frame the whole issue as merely a ‘conflict,’ they figure they don’t need to focus on justice or accountability. Instead, they think, the problem can be solved by getting the abused and the abuser in a room together where everyone confesses their sins” (p.70).

Kruger lays out several principles to keep in mind as churches seek reconciliation between abusive pastors and their victims:

- Victims should not be asked to meet with an abusive pastor unless he has been held accountable.

- Victims should not meet with an abusive pastor unless he is genuinely repentant. I would note that this should include an oppressive leader naming his abusive/power/control behavior.

- Victims should not meet with an abusive pastor until they are emotionally and spiritually ready. (pp.70-74)

Getting the abused and the abuser in a room together is often not helpful in spiritual abuse situations absent these three conditions because there is a high likelihood of re-traumatization and further oppression of victims through the mediation process. Victims are likely to be abused again by the abuser as he uses the system and process for his benefit, and this is not always easy to detect by the others in the room.

“If victims of abuse refuse to meet, an unrepentant pastor will likely portray the victims as unforgiving and unwilling to reconcile. He will take the moral high ground, making himself out to be the peacemaker and the victims as the ones holding a grudge. This is why it is imperative that churches not even ask the victims to meet with the abuser until the guidelines are met. That way, the church is preventing the meeting from taking place, not the victims” (pp.72-73).

Mediation or Investigation?

Where spiritual abuse is alleged or suspected, it would be wise for Christian conciliators to not jump into promoting mediation, even if the request for mediation is at the request of a pastor or elder board. Those in power or footing the bill should not get to control the mediation process. This may mean that we have to turn down paying clients. Instead I would consider making a recommendation for an independent investigation to be done by a third party. Kruger agrees: “When a church is faced with credible claims of spiritual abuse, the standard practice should be to hire an independent, outside organization that understands how to investigate abuse cases properly” (p.127).

To be truly independent, the church can not control the investigation process or which findings are released. Kruger explains that getting outside help does not supercede the authority of an elder board or presbytery, rather it acknowledges that blind spots may exist and that experts can be helpful in diagnosing a problem and making helpful reports and suggestions to a church.

How can we be sure that people aren’t just inventing these stories, that it’s not just a misunderstanding? Statistics show that false claims of abuse are rare (p.88) and there is an enormous price for whistle blowers who are not believed, have their character attacked, and driven out of the churches they love. “What would motivate them to lie about the charges? What would they have to gain? Often they have everything to lose” (p.88). In fact, Kruger points out that bully pastors will leave a trail of injured victims. “If multiple people have stepped forward with similar stories and claims, then their credibility goes up considerably” (p.89).

Understanding Our Limits

Abusers want peace with those they hurt, without repentance and accountability. Christian conciliators and those helping victims need to understand their limits in bringing about reconciliation. Reconciliation can not take place without repentance coming first. Repentance is a work of the Holy Spirit. As Darby Strickland has stated, we can not solve oppression and make it stop. Yet, our Lord sees all injustice and will bring justice and shalom to his people.

As James 3:17 states, the wisdom of God is first of all pure and then peace-loving. We can not have true peace in our churches until we first have purity and righteousness. With a well-formed understanding of spiritual abuse, Christian conciliators can help others find true peace with God, not allowing abusers to claim “Peace, peace,” when there is no peace.

Don’t Be Fooled by False Repentance

Here it’s important to know that abusers are good at impression management. They are good at deflecting blame to others and offering concessions for change, dangling hope so others recommit to the abusive system. Wade Mullen’s book “Something is not Right” talks about how abusers are good at putting on a show and impression management. You can find my book review of that book here.

Impression management often looks like “repentance”; however, when examined more closely, the way abusers repent often leads to more abuse. I previously wrote about true and false repentance and stated that, “We should hate when churches exhibit cheap grace and abusers get away with their oppression.” Calling an abusive pastor to account and calling them to true repentance is loving to them. Letting a fake show of repentance pass for the real thing is unloving.

Where an abuse of authority has taken place and there is true repentance, an abuser will willingly step down, accepting consequences for his actions, revealing the full truth, and wanting justice to be done. Pastor Tom Pryde talks about recognizing a repentant abuser here. As a Christian Conciliator, one question I would ask a church is, “Do the victims believe there is true repentance in an abusive pastor?” And even if there is true repentance in an abuser, this does not mean there are no consequences for an abusive pastor’s actions and broken trust.

The humility that accompanies true repentance breathes life to the whole congregation, including his victims. However, what we more often see, is the tendency for a proud abuser to retaliate and try to control the victims even more. It’s as if he punches his victims when they are down and then gets others to comfort him because his fist hurts so much. But make no mistake, an abuser’s sin is not that he didn’t control others properly, but that he failed to control himself. Abusers lacking in self-control will seek to control others.

Conflict Coaching as a Tool to Help Victims

While abuse situations don’t usually warrant mediation, conflict coaching is a service Christian conciliators can offer to victims to help them move towards healing. Some themes that could be helpful to cover in conflict coaching would be (1) Understanding and Anticipating the Retaliatory Tactics of Abusers, (2) Being Grounded in Reality & Dismantling the Gaslighting, (3) Reclaiming Biblical Language with Proper Definitions, and (4) Helping Victims Process Their Emotions.

Understanding and Anticipating the Retaliatory Tactics of Abusers

Just as you wouldn’t expect a survivor of physical or sexual abuse to express their accusations perfectly, so we cannot expect a survivor of spiritual abuse to perfectly define or explain their abuse. They will likely lack the perfect balance of grace and rebuke, compassion and hard truths, love and concern. That’s ok. There is a place for reflection and consideration of how victims can respond to abuse in a more Christ-like manner, but in this stage the focus should be more on safety and getting the victims to a place of healing. Whether a victim or advocate calls out the abuse semi-privately to others in leadership or publicly to an entire church, retaliation from the abuser is a likely next step.

In chapter five on the retaliatory tactics of abusers, Kruger showcases the lengths an abusive pastor will go to justify himself and attack those who confront him. Abusers are driven primarily by both insecurity and entitlement, so when confronted, their responses are remarkably predictable. Personally, I’ve seen a pastor who was accused of abuse respond as if chapter five of Kruger’s book was a script written just for him.

When a truly abusive pastor is charged with abuse, he will do things like insist that a proper process like Matthew 18 wasn’t followed (p.80); he will flip the script and not only declare his innocence but accuse victims and those concerned about abuse as slanderers (p.84); he will also attack the character of victims (p.89), tout his own character and accomplishments (p.93), and play the sympathy card (p.94).

“An abusive pastor’s first step is to build a strong coalition of allies who can speak up for him, defend, him, and even go on the offensive against the victims” (p.79). Kruger notes how this coalition building is usually done even before an allegation might arise. The pastor builds up a team of elders and leaders who are devoted to protecting him. When an accusation comes to light, he will often get his story out first to control the narrative. Then, his loyal followers, often blinded by his charisma, zeal, and good works, will become aggressive and uninformed defenders of their pastor. So we see that, “Spiritual abuse is allowed to continue because willing supporters protect and enable that pastor” (p.80).

Kruger also mentions that an abuser will attack the character of victims. He will label them as divisive. He will call them slanderers. He will call them deceivers. He will be selective in the truths he shares about the victims or go so far as to make up lies and use past sins against them. He will use church discipline in attempts to control and punish them. Remember, a victim should not need to be sinless to warrant not being abused, just like criminals don’t deserve to be abused by police.

When facing retaliation, victims can be encouraged with passages such as Matthew 5:11-12 and 1 Peter 3:8-17. Peter calls us to love our enemies even when we are slandered and reminds us that our call to suffer for righteousness’ sake is a call to walk in Christ’s footsteps.

Being Grounded in Reality & Dismantling the Gaslighting

When conflict coaching with victims, we need to help them see through the fog and narrative-twisting of abusers to see what is true. The biggest help Christian conciliators can offer to victims is to help them process what is happening to them in a safe environment.

The truth is true, no matter if others in the congregation choose to believe what they prefer to be true. The truth is true, no matter how an abuser tries to re-write history (gaslighting) or reframe the narrative. It is in living in truth that victims can find freedom from oppression.

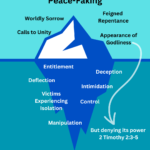

We may be helping victims see the sinfulness of sin. This may include helping victims to recognize the entitlement and coercive control that abusers have and helping them to see that the tools of an abuser include isolation, deflection, manipulation, and intimidation.

When dealing with abuse victims, be prepared to be patient. The deflection and manipulation of an abuser often leads to victims thinking they are responsible for the problem, not their abuser. It can take a while for victims to fully understand what has happened to them.

Reclaiming Biblical Language with Proper Definitions

We may need to gently help victims dismantle and reconstruct definitions and spiritual concepts that have been twisted and abused, concepts like submission, grace, forgiveness, repentance, authority, peacemaking, slander, gossip, and what is meant by Matthew 18.

We may need to help victims understand what submission to proper authority looks like and help them to understand the fallibility of men. We may need to help victims reclaim agency and think through how to exercise their own conscience rather than simply doing what they have been told to do or think.

We may need to help victims understand their worth by showing them that God is for the oppressed and hates abuse. Or we may be helping a victim see that God has not rejected them despite being wrongly placed under church censure or excommunication. One pastor offered this encouragement: “One of the most pastoral statements in our confession is that church courts can err.”

Kruger gives attention to one word that gets easily mangled in abuse situations and therefore should be clearly defined for victims and churches: slander. Here Christian conciliators would do well to help people understand what slander is and what slander is not.

How can churches or Christian organizations avoid creating a culture where people are afraid to speak up? First, they need to make sure they have the correct definition of slander. While the term is frequently used, it is often misunderstood. Slander is not merely saying something negative about another person. Rather, it is saying something negative while knowing it is false (or at least having no basis to think it is true). In other words, slander involves a malicious intent to harm another person’s reputation by spreading lies about them (2 Sam. 10:3; 1 Kings 21:13; Prov. 6:16-19; 16:28; Ps. 50:19-20).

Here we should pause and consider that slander is a very serious sin. To lie about another person is something the Lord hates (Prov. 6:16). Such lies can destroy a person’s reputation and ministry. But telling the truth is not slander. To speak up about a pastor’s abusive behavior—in appropriate ways—is not slander.

There is a rich irony, then, when the accused pastor offers a strong countercharge of slander. If he has no evidence that the accuser is lying, then the pastor himself may be guilty of slander. In other words, the pastor expressing concern over unjust accusations may actually be making an unjust accusation against someone else. And when the pastor’s defenders repeat the claim that he is a victim of slander—without any evidence that the accusers have malicious intent—then they too may be guilty of slander (pp.86-87).

Kruger goes on to talk about gossip, the twin sister of slander, (p.87) and explains that it is not gossip to talk about your experience as you try to process it and get help. Gossip is problematic when true information is shared with malicious intent. But just because something is negative about a person does not make it gossip. You can read here for more on the topic of gossip.

Helping Victims Process their Emotions

When conflict coaching with victims, we may need to help a victim become more self-aware of their emotions such as grief, anger, fear, or guilt.

We may be helping victims with godly emotions such as grief. The Psalms are full of God’s people crying out to the Lord against injustice. It is right and proper to have grief over the destructive nature of sin and to lament the misery of sin, asking God to intervene for his people.

It is not uncommon to find fearful or angry victims. Conciliators need to be careful not to mistake fear in victims as a lack of faith or anger in victims as mainly sinful anger.

We want to help the abused reclaim their moral agency and voice so they are not fearfully responding to the control tactics of an abuser. As 1 John 4:18 states, “Perfect love has no fear.” To love an abuser well, we have to be fearless of them. We have to fear God more than we fear our abuser.

Proverbs 29:25 states: “The fear of man lays a snare, but whoever trusts in the Lord is safe.” It is when victims are fearless of man and fear God that they can truly be free in Christ and free from the tyranny of man.

We may need to help victims with false guilt. Nothing they did made them deserve to be abused. Abusers are good at getting victims to feel the weight of responsibility for a conflict. Abusers flip the script and portray themselves as the victim, pointing out other’s sins without taking true ownership of their own sins. Abusive pastors put heavy burdens on people’s shoulders (Matthew 23:4). Victims should not take responsibility for the sins of their abuser. Instead, they should take responsibility for only the sins they have committed in the process (such as sinful reactions and responses), and find freedom in the forgiveness of Jesus at the cross. We can also point them to the hope of their union with Christ. Christ rages at abuse and takes attacks on his people personally (Acts 9:3-5).

We may need to help victims by asking the question, “What does love look like?” We can help victims understand what love of their pastor or even love for their enemies looks like. We may be helping victims understand the difference between enablement and accountability. Kruger even asks this question of himself as he considers the need to write this book.

“We can convince ourselves that loving the church means keeping our mouths shut about its weaknesses. But what if that’s not what it means to love the church? What if loving the church means we want it to be sanctified so it reflects Christ’s beauty even more? What if loving the church means loving the sheep—whom Christ loves—and guarding them against the wolves Christ asked us to watch out for? What if loving the church means addressing the things that mar its reputation in front of a watching world?” (p.17-18).

Closing and Resources for Further Study

Kruger’s final chapter focuses on how to prevent abuse and create church cultures that resist abuse. While well-intended, I think the efficacy or practicality of some of his suggestions are debatable. The recommendation I would most emphasize is when Kruger advises that elders and church staff need formal training in spiritual abuse (p.123). I believe Christian conciliators and peacemakers can benefit from abuse training as well. Most people have a better estimation of their own abilities to recognize and identify abuse (even without training) than is actually true.

If you want to grow in your understanding of abuse, here are a couple places you might start. Even though these resources are not limited to spiritual abuse, the principles still apply. My favorite course was Psalm 82 Initiative’s 4 Tools Course to learn how to spot and identify abuse. You can start with Psalm 82 Initiative’s article on Untangling the Abusive Relational System, see some of his free videos, and register to take his online class for further education. Churchcares.com also has a number of free videos to help train churches to care for victims well. Freeing the oppressed is a gospel issue and is near to God’s own heart (Ezekiel 34:1-24, John 10:10-15, Psalm 82:1-8, Luke 4:17-19).