In his book Bully Pulpit: Confronting the Problem of Spiritual Abuse in the Church, Michael J. Kruger, does a great job shedding light on the problem of spiritual abuse, defining it, surveying Scripture for wisdom on the topic, and explaining the tactics of abusers. Dr. Kruger is President and Professor at Reformed Theological Seminary in Charlotte, NC. He argues that spiritual abuse is a very real category of abuse and a problem that needs to be addressed in churches of all kinds today.

This is admittedly an unusually long blog post for Be Reconciled, but I wanted to do justice to the important topic of spiritual abuse. In Part 1 I will summarize key takeaways from the book, and in Part 2 I will highlight some helpful principles for Christian Conciliators and look at how to most helpfully engage those in conflicts that involve spiritual abuse. While Kruger writes as a leader in the church to other leaders with the aim of stopping and preventing abuse, his book is a good introduction to the topic of spiritual abuse for the average church member also.

As a Certified Christian Conciliator, I’ve come to understand the limits of mediation for abuse situations in marriages, and now I’m beginning to see the limits of mediation for certain types of church conflicts. Most people would agree that to have a victim of physical or sexual abuse meet face to face with an offender in a mediation session would be unwise. It would be unjust and unsafe. But what about those who have been spiritually or emotionally abused? Would mediation work in a spiritual abuse situation? I will consider this question more fully in this review.

Spiritual Abuse: Not a New Problem

Kruger goes through Scripture passages and shows that the problem of abuse is not new. The Israelites wanted a king to rule over them but many of these leaders were harsh and abusive. “They wanted the typical worldly profile of a leader: one who is strong, tough, dynamic, and powerful. They would rather have a leader to beat up their enemies than one who would care for the sheep” (p.44). A prime example of this, Kruger notes, is King Rehoboam who dealt harshly with his people by placing heavy burdens on them (p.45).

Some priests were also abusive, including Hophni and Phinehas (p.47). These spiritually abusive leaders were busy feeding themselves rather than feeding the sheep. Not only were these two sexually abusive, but they took the choice meat for themselves instead of offering it to the Lord. The sheep who dared raise their voice in protest of their abuse of power were met with coercive tactics (1 Samuel 2:16).

Though Kruger doesn’t mention it, in Scripture, we see also the retaliation from an abusive church leader in 3 John. The Apostle John is writing to encourage his pastor friend Gaius and mentions his intention to publicly oppose Diotrephes, who could be considered a bully pastor:

“I wrote to the church, but Diotrephes, who loves to be first, will not welcome us. So when I come, I will call attention to what he is doing, spreading malicious nonsense about us. Not satisfied with that, he even refuses to welcome other believers. He also stops those who want to do so and puts them out of the church” (3 John 9-10).

In this example, Diotrephes maliciously spreads gossip and slander about those who would accuse him and puts people out of the church whether through implicit pressures or the means of explicit church discipline on anyone who crosses him. It is not much different with bully pastors in this generation. As the writer of Ecclesiastes notes, “There is nothing new under the sun.”

Kruger gives this encouragement,

“God will hold accountable not only the bad shepherds but also those who protect and enable them. This is a weighty warning to all churches and the elder boards that lead them. Those who prop up bad leaders and turn a blind eye to their abusive behavior will someday have to give an account for their own actions” (p.48).

But not only does God promise to judge the bad shepherds, he promises he will be the new and better shepherd of his sheep (Ezekiel 34:15, John 10:11). What hope we can offer victims of abuse!

Kruger points out that the New Testament qualifications for elder focus on character over giftedness or knowledge. He covers passages such as Mark 10:42-45, 1 Timothy 3:3, Titus 1:7, 1 Peter 5:2-3, 2 Timothy 2:24. God’s qualifications for elders include that they be kind and gentle, lowly and humble (pp.48-59). In some ways, the problem of abusive pastors is a problem of congregants getting what they ask for and idolize, so calling an abusive pastor to repent is calling the whole church congregation to repent, to turn from their idolatry and their enablement of abuse to seeking righteousness and faithfulness to God’s word.

What is Spiritual Abuse?

So how do we recognize spiritual abuse? Kruger explains:

“Spiritual abuse is when a spiritual leader- such as a pastor, elder, or head of a Christian organization – wields his position of spiritual authority in such a way that he manipulates, domineers, bullies, and intimidates those under him as a means of maintaining his own power and control, even if he is convinced he is seeking biblical and kingdom-related goals” (p.24).

Kruger explains the three hallmarks of his definition. First, for spiritual abuse to exist, there must be ecclesiastical or spiritual authority over another. Second, the “abusive pastor uses sinful means [e.g. hypercriticism, cruelty, threats, manipulation, and deflection] to control and dominate those under him” (p.28). And finally, an abuser appears to be building God’s kingdom when he is really building his own kingdom to preserve his power and authority.

The deceptive nature of abuse is that even abusers can do good things and genuinely help a number of people. At the same time, he may also be self-deceived and harming others.

“In his mind, he is so significant to the work of the kingdom, so important, so valuable that he feels justified in doing nearly anything to keep that ministry on track. If people get run over, then that’s because they got in the way of the great kingdom work he’s doing – collateral damage, so to speak. In a sick, twisted way, he is crushing people for the glory of God” (p.34).

What Does Spiritually Abusive Behavior Look Like?

Kruger defines and gives examples of abusive behaviors by bully pastors: repeated patterns of being hypercritical, cruel, threatening, defensive, and manipulative (p.28-32). It could be cutting people off in a meeting, publicly embarrassing someone over a mistake, speaking harshly, terminating employment or removing lay church leaders who are not fully supportive of the bully pastor, using church discipline as a weapon, or threatening to ruin a person’s reputation. It’s also important to note that an isolated incident of these kind of behaviors doesn’t mean someone is abusive; rather it is when a pattern emerges of these types of things that there should be serious concern.

Fear and intimidation is another common tool of abusers. “Fear is one of the most potent weapons in the hands of an abusive pastor. Members of the church are often afraid to speak out because they know what happens to those who do” (p.99). One friend of mine who was being abused by his pastor was visibly shaking even just talking about the pastor in front of me. I noticed the high level of anxiety he had at the thought of meeting with his pastor. It was not a safe place. Consider that when a congregant displays these physical signs about the prospect of meeting with his elders, it is not a sign of his weakness, but a sign of his body’s reaction to the oppression he may be facing.

“Here’s the point: It is not normal for people to have this sort of fear of their pastor. We need to let that sink in. If many people, across many years, express significant fear of a pastor, then something is very, very wrong” (p.31).

Spiritual Abuse Involves the Misuse of Biblical Concepts

Spiritually abusive behavior is not limited to worldly tactics. Biblical concepts such as confession might become weapons of coercive control and intimidation. “In fact, many abusive churches encourage members to openly confess their sins, insisting that they dig down deep and reveal their darkest secrets. Tragically, once they sins are confessed, sometimes under coercion, they are later used against church members who step out of line” (p.30). Confession for the Christian should bring freedom in Christ, but for the abusive pastor confession becomes a tool of bondage, manipulation, and intimidation. Kruger notes the tendency of abusers to use the pulpit to attack victims, preaching in ways that target a specific victim while most of the congregation is oblivious to the attack (p.27).

“Sadly, such tactics are not that different from those employed in the most disturbing non-Christian abuse cases… The difference here is that the abusive pastor can always hide behind the excuse that he was just ‘confronting sin’ in those under him. And tragically, many elder boards accept that excuse” (pp.30-31).

It is not that they confront sin but it is the manner in which they confront sin. Other times a bully pastor will simply be flat out wrong about the sin they are attempting to confront (p.38).

Abusive pastors often remind people of their authority (p.31) and appeal to scripture in doing so. While the Bible is not anti-authority, we should be aware of the tendency of abusers to power-posture. Bully pastors will use Scripture to impose on people’s consciences. This can be tricky to spot because the pastor may even be theologically correct in their own convictions on a particular issue, but the way those convictions are applied to other church members leaves no room for individuals to have freedom of conscience.

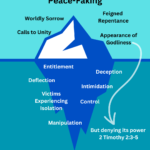

Spiritually Abusive Behavior Involves the Misuse of Biblical Peacemaking

For abusive pastors, even calls to “peacemaking” can be used as a tool to silence victims. In one abusive church, the pastor had Peacemaker brochures in his office, much like this brochure promoted by RW360, which is actually a great tool when used rightly!

Christian conciliators need to be aware of the potential abuses of Matthew 18. An accusation of abuse is different than a conflict that would fit the example of Matthew 18, but abusers will make Matthew 18 apply to any and all conflicts, offenses, rebukes, and accusations as it suits them, so if victims speak to others about their experience they have a high risk of being accused of gossip. The victims are kept from talking to anyone else about the problems they experienced, except by going to the pastor directly and oftentimes, alone. Conciliators need to recognize that calls to “Biblical peacemaking” can really be a tool to isolate victims, keep them from talking with the other elders, and deflecting blame to victims.

Kruger gives some helpful remarks about the abuse of Matthew 18 in his book (p.80-84). (For other resources: The abuse of Matthew 18 is documented here. Professor Keith Evans of Reformed Presbyterian Theological Seminary rightly notes, “Matthew 18 is not speaking of abusers and oppressors.”) One victim of spiritual abuse lamented the isolating effect of Matthew 18 to me, “If I’m following Matthew 18 the way they want me to, how does one ever get to 1 Timothy 5:19-20? It’s in the Bible, but their process completely removes that from the realm of possibility.” He was referring to the passage that calls for bringing a charge against an elder on the basis of two or three witnesses and those elders who persist in sin to be rebuked in the presence of all. If he could only ever talk to the abusive pastor about his concerns and perhaps another elder who is a defender of the abusive pastor, how would he ever get multiple witnesses?

The Impact of Spiritual Abuse

Kruger talks about the wounds of the abused including emotional, physical, relational and spiritual impacts.

- Emotional Effects: Emotional impacts include fear, anger, shame, depression, and PTSD. Kruger cites studies showing that emotional abuse and neglect can be just as devastating as physical and sexual abuse (p.102).

- Physical Effects: Spiritual abuse does affect the body and can lead to a number of physical ailments consistent with PTSD such as heart problems, fatigue, and even auto-immune disorders. Others have noted the connection between emotional abuse and physical abuse and the connection between our bodies and souls here and here.

- Relational Effects: Kruger talks about the relational effects (p.103) of spiritual abuse, one of which is ostracization. “The trauma of this sort of social ostracization is bigger than just the victims missing their former church. It involves the reality that their former church has now been turned against them and now regards them as divisive, troublesome, and slanderous” (p.104). Even if church members don’t actively shun the victims, but chose to stay for the sake of avoiding conflict, they too are in passive support of the actions of the pastor. Oftentimes, church members wish to remain “neutral”, but in reality “not taking sides” is not a real possibility. By staying at the church and continuing to listen to the leader and pay their tithe money, they have clearly chosen a side and act in a way that legitimizes the abusive leader as though nothing were wrong. Victims of abuse talk about losing many of their closest friends at the time they most need encouragement and support from the body of Christ (p.105).

- Spiritual Effects: Finally, Kruger talks about the spiritual effects of abuse and the “most damaging effects that spiritual abuse has on victims: it often crushes a person’s spiritual life and calls into question all they believe” (p.106). This can include include doubts about the church, Christianity, God, and themselves.

As Christian Conciliators, we need to be particularly gentle with the spiritually abused, helping them to see their value and worth and being careful in our use of Scripture so that victims hear the voice of the Good Shepherd, not the voice of their abuser. It is truly a privilege to walk with the oppressed, showing them that the characteristics of the True Good Shepherd may be different than what they have been led to believe by the example of their abuser.

Holding Spiritual Abusers Accountable

Kruger calls for bully pastors to be held accountable in churches and Christian organizations big and small. Like abusive police officers who bring reproach to their vocation, bully pastors are disqualified from the ministry, no matter how important they may seem to themselves or others. “Ironically, it is this misguided desire to protect the office that may actually be harming it. The dignity of the office would be better protected if more good police officers had the courage to stand up to the abusive ones” (xvii, introduction).

Kruger points out that the high profile spiritual abuse cases like those from Mars Hill Church should not override the seriousness of the problem of spiritual abuse in smaller congregations or less influential pastors. The issue is whether or not there are bleeding sheep, not the status or notoriety of the abusive shepherd.

Kruger points out that there is a sort of theological misunderstanding of grace that attempts to “flatten out” sins in a sort of sin-leveling (p.68). “If we are all equal sinners, it is argued, then we should give these abusive pastors a break. They are sinners, just like the rest of us” (p.69). The argument is that we need to show them grace as we have been shown grace. But this theological error forgets that some sins are worse than others. “While all sins are equal in their effect (they separate us from God), they are not all equally heinous” (p.69). We don’t talk about giving police officers who abused their authority second chances with that kind of power. It is in the nature of love for an abuser to have consequences for his actions and to call them to repentance.

Kruger notes, “Abuse is contrary to Scripture and disqualifying for ministry” (p.130). While spiritual abuse ought to be disqualifying for Christian leaders, sadly many of these leaders remain in their positions for a long time even after accusations of abuse have come forward.

Kruger’s book doesn’t go into detail about exactly how and when to hold an abusive spiritual leader accountable, though the question naturally arises. Kruger’s book is a bit more diagnostic rather than giving advice to how victims may best respond once they understand they have been spiritually abused. This is partly due to the fact that the wide variety of situations church government/accountability structures will lend themselves to different approaches. We also have to understand that some victims don’t have the safety or strength to speak of their experience to those who have the authority to hold an abuser accountable or to confront an abuser directly, but by God’s grace and perhaps through the support of advocates, some will find the strength to speak the truth, even if no one else believes them.

Next Time

Now that we have a foundational understanding of spiritual abuse, in Part 2 of our book review (now available), we will look at how Christian Conciliators and peacemakers can apply this to their practices.